Martha Young author of “The Real Song of the South”, Collected folktales and living voices human and animal alike, Absorbed the speech its cadence and energy of black storytellers

From O’Henry Magazine August 2018.

“The Real Song of the South

How an eccentric Alabama spinster collected folktales and living voices — human and animal alike — from an age that is gone with the wind”

“We scrambled flat on our stomachs, wrestling the bulky cardboard box from under the looming four-poster bed. My cousin Anne and I are not teenagers . . . we’re not even middle-aged . . . so it was a grim spectacle of struggling grayheads, who risked never getting vertical again, to do this.

The musty papers and letters of one of the most colorful of our relatives, our great-aunt, Martha Strudwick Young, a diminutive professional writer, born the year after the War Between the States began, contained some surprising new information. Cousin Anne had never looked in the boxes since her mother’s death in 1970, some 40-plus years ago. We were only a few miles from Martha Young’s birthplace in Hale County, Alabama, at a place called The Pillbox a few miles out from Greensboro, Alabama, and my visit had prompted questions about the writer’s childhood. We were well into the second round of iced tea when Anne remembered the flat coat box stored beneath the bed.

We knew from family stories that Martha’s early years were spent riding in the carriage with her father, Dr. Elisha Young, through the Hale County countryside as he made his rounds and tended to his patients. A surgeon in the Confederate Army stationed at Fort Morgan in Mobile — and imprisoned in New Orleans after the fall of Mobile — Dr. Young returned to his little family after the war to practice medicine in Greensboro, Alabama. A born storyteller, the doctor entertained the little girl with stories of making quilts with his black nurse as a young boy, eyewitness accounts of battles on Mobile Bay, and starving troops in the Alabama countryside as the father and daughter roamed the county in his buggy on house calls. He told of performing the first ever successful cutting and suturing of a carotid artery on a man stabbed and brought to his kitchen table in the middle of the night. The patient survived the procedure in the makeshift operating room. Dr. Young said that early quilt-making, common among young Southern boys in the 1860s in the county, gave him his surgical skills.

Martha had a quick ear for the rich dialect of the black folks at home and in the rural countryside. She was spellbound with their musical language and loved their tales of witches, wicked spells and ha’nts, and stories of talking birds. She absorbed the speech, its cadence and energy, of the black storytellers. Martha took mental notes on the actual calls and songs of birds of her native Hale County along the wooded roads. She was a good listener and had an excellent ear for mimicry.

She began to write and craft the oral tales told to her by blacks in her household and those she knew in the small community of Greensboro. She listened to the musical calls from the men and women who peddled fresh butterbeans and field peas ( “Fe-ull Peeas. Yas. Freee-sh Pleeeez . . .”) from carts on the dusty streets of her neighborhood. She listened to the ghost stories of the cook Chloe in the family kitchen house and to the animal stories of Isham, who helped with the horses and cows. She wove the tales into lyrical and haunting stories about sparrows’ chatty conversations with crows and baby robins squabbling among themselves. And useful warnings that picking peaches from the tree after sundown would kill the tree. Martha added her own keen observations of nature in Greensboro and the countryside around it, and incorporated the sounds of the birds and creatures as an integral part of her stories.

Being the oldest child of the eight siblings (of whom only five survived), Martha as a young adult in her 20s inherited the role of caretaker of the family at her mother’s early death in 1887. Her physician father could never have managed without his eldest daughter’s capable and no-nonsense discipline of her younger, motherless brothers and sisters. Martha practiced her bird calls and storytelling skills on the younger children, who were enthralled at their big sister’s tales of the talking buzzards, singing bats and swamp witches. Amazingly, she continued her writing despite being mistress of a large household and surrogate mother to a brood of children ages 7 into pre-teen.

And after raising her younger brothers and sisters, Martha, or Tut (rhymes with foot), as the family called her, decided that the single life was the life for her. As she always replied to inquiries about her marital state: “No, I am not married. I shall stay . . . forever Young!” (Her early sibling-rearing may explain the decision of the many spinsters out there, especially around the turn of the century.) Granddaughter of an Alabama anti-Secessionist, she had a college degree and was encouraged in her writing by her family. She started her career under the pseudonym Eli Shepperd, since young women from the South were not usually accepted in the male-dominated literary scene.

She began submitting her dialect bird stories to the New Orleans Times-Democrat, which first published her work in 1884, a Christmas story titled “A Nurse’s Tale.” Other Southern newspapers published the prolific writer’s stories.

The creator of Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby, Joel Chandler Harris, gave high praise to the dialect writer, according to one newspaper account and even collaborated with Martha on one of his Uncle Remus collections. Joel Chandler Harris himself wrote: “Her dialect verse . . . is the best written since Irwin Russell died. Some of it is incomparably the best ever written.”

Her first book, with the catchy title Plantation Songs for My Lady’s Banjo and Other Negro Lyrics and Monologues, was published in 1901, still under the pseudonym Eli Shepperd. The originator of Brer Rabbit contacted the writer under that name. Joel Chandler Harris invited “Mr. Shepperd” to join him at a small hunting lodge at his Georgia home, Eagle’s Nest, to work on a collection of folk stories. It was a secluded spot and Harris felt it would be a productive collaboration. Naturally, Martha revealed her identity as a lady and responded that she hardly thought that Mrs. Harris would approve the plan. The two writers did eventually collaborate, but not in the secluded setting first suggested to Eli Shepperd!

More books followed Plantation Songs: Plantation Bird Legends (1902), Bessie Bell (1903) (later re-released as Somebody’s Little Girl in 1910), When We Were Wee (1912), Behind the Dark Pines (1912), Two Little Southern Sisters (1919), and Minute Dramas: Kodak in the Quarters (1921). Another Martha Young book, Fifty Folklore Fables, was reviewed and mentioned in publicity releases but is unable to be located. Plantation Bird Legends and Behind the Dark Pines are both illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings by J.M. Conde, the artist used by Joel Chandler Harris. Besides her eight published books, numerous articles and stories by Martha appeared in such magazines as Woman’s Home Companion, Cosmopolitan and Christian Advocate. Cosmopolitan, begun in 1886, was a family magazine at the time (a far cry — not even in shouting distance — from the modern Cosmopolitan) and featured such established writers as Jack London, Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser and later H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw. (In 1965, Helen Gurley Brown, author of Sex and the Single Girl, revamped the family magazine of Martha’s day, zeroing in on women’s issues, becoming the familiar magazine we know today as the sexy Cosmopolitan.)

Martha Young reached her literary peak in the first decade of the 20th century. Her whimsical bird stories in African-American dialect were a runaway hit. Her books were a smash across the country, North and South. The Pittsburgh Gazette was among those who raved about her Plantation Bird Legends: “What the Grimm Brothers did, taking from the lips of unlettered peasants the folktales of the foretimes and setting them down for the delight of the after age, has now been done by Miss Young.” Martha’s other animal tales included such titles as “Why Brer Possum’s Tail Is Bare,” “Mr. Bluebird’s Debt,” and “Why Mr. Frog Is Still a Batchelor.”

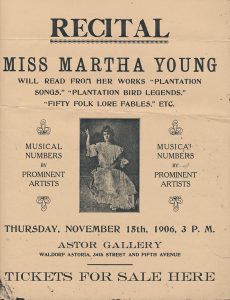

Martha even performed live at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1906, reading stories and poetry in dialect from her published books and actually performing bird calls and trills to the audience’s amazement and delight. Other “musical numbers by prominent artists,” not mentioned by name, were also to appear on the evening program. She became a popular speaker in the East and almost all reviews of her events laud her delivery and lively presentations with comments about her distinctive voice.”

Read more:

http://www.ohenrymag.com/the-real-song-of-the-south/