Martin Luther on vocations, God created 3 orders: ecclesiastical, civil, economic, All Christians have a vocation to serve God in their household and economic sphere

Luther and the Lutheran Confessions on Vocation

John A. Maxfield

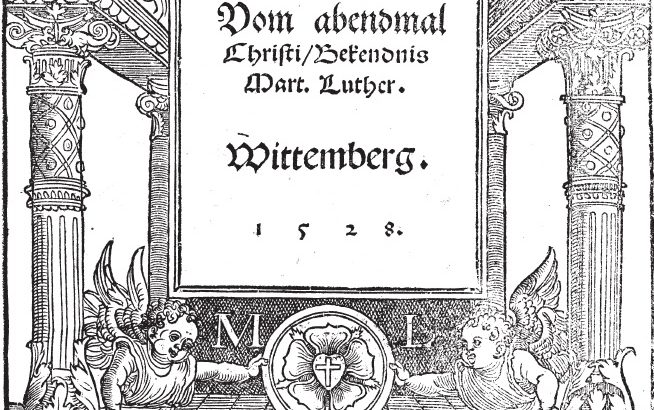

“This essay is an investigation into how the Lutheran Reformation treated the subject of a Christian’s vocation. I introduce this investigation by referring to this confession of Luther’s faith because this text clearly reveals the Reformer’s own treatment of the chief articles of faith, including his understanding of the Christian’s vocation, in the form of a written testament for posterity, much like the later Smalcald Articles. In the midst of so many genres of Luther’s writings—from polemical treatises to sermons and biblical lectures to catechetical treatises to personal letters—the testamentary writings of Luther stand out as the Reformer’s own statement of what he wanted posterity to view as his confession of the gospel and of Christian doctrine.”

Luther’s view of justification turned this ethical system on its head and placed Christian ethics into two realms of life in God’s world. In the divine realm, or right-hand rule of God, Christian righteousness is something that proceeds from faith alone and is therefore impossible apart from faith. No matter how good a person is in terms of ethical behavior (what the Lutheran reformers call human righteousness), such a person has no Christian righteousness without faith in Christ, from which Christian righteousness blooms as fruit from a good tree. On the other hand, while the Christian living by faith already has perfect Christian righteousness according to the principle of simuliustus et peccator— simultaneously totally righteous and totally a sinner—such a person nevertheless still has to work very much at ft to develop good practices of ethical behavior in the other realm, the realm of human righteousness, or God’s left-hand rule. Like the unbeliever, Christians are accountable for their actions in this realm of existence, and they cannot simply appeal to forgiveness to remove from themselves that accountability. In the realm of human righteousness, also known as civil righteousness, the Christian is not essentially different than an unbeliever who is striving to live a good life. In fact, as I will later show, Luther views the works even of godless, unbelieving men as the holy work of God in the world when these people are participating ethically in the left-hand rule of God, through the orders that God has established for the preservation of his world.”

“But first we need to wrestle with the way Luther viewed the

worldly vocations of Christians as outlets for Christian righteousness.

This is indicated by the fact that in his 1528 Confession,

the Reformer placed his discussion of vocation with in the

second article o f the Creed. Indeed, so central is the doctrine

of vocation to Luther’s understanding of Christian righteousness

that within this section of 112 lines (in the critical edition)

devoted to Christ’s person and work, the Reformer devotes 77

lines, or about two-thirds of the whole, to the righteousness

Christworks in the lives of believers, a righteousness that is

wholly Christ’s work and gift, and yet it is a righteousness that

Christians participate in through their daily life in the world.”

To these humanly devised religious institutions the Reformer contrasts the “holy orders and true religious institutions es- tablished by God… : the office of priest, the estate of marriage, the temporal authority.”5 Here we come across the three orders of God’s creation that are sometimes referred to as the three hierarchies; in Latin texts, Luther uses the terms ecclesia, oeco- nomia, and politia. Not just the priesthood or pastoral office but the whole order of life and office in the church is one of the sacred orders that God has created in the world. Not just marriage but the whole order of life in the household and the economic sphere of labor and production is likewise an order created by God in which his people can live out the life of faith and holiness. Not just political offices but the whole civil order with all its relationships of rule and obedience, patronage and service to the state—this is a realm in which the Christian can serve God by faith, and such service is a holy work of God when it is done in conformity with the word of God, in particular when it is done by faith.”

“Luther here defines the various places where sanctification and the Christian life are pursued as places where Christian love for the neighbor can be put into practice. The holy life takes place in the household, where parents carefully raise their children to serve God according to his word. The holy life takes place in the civil realm, through wise governance and obedience to civil laws. In short, for Luther the holy life does not take place in the myriad of religious activities that human beings create and pass down as traditions of the church, but rather in the activities that God has prescribed in the created order itself. And love is what binds these orders together—not just any love but Christian love, which is the fulfillment of God’s law (Rom 13:10). The Christian lives a holy life when in his or her vocation—comprised of church, household and work, and activities in the civil realm—God’s word is upheld and honored, all under the overarching practice of Christian love.”

Read more:

https://twokingdoms.cune.edu/files/2016/02/Luther-and-the-Lutheran-Confessions-on-Vocation.pdf