Tommy Thompson obituary, Charles William Thompson, Red Clay Ramblers founder, 1977 interview

From the UK Independent February 18, 2003.

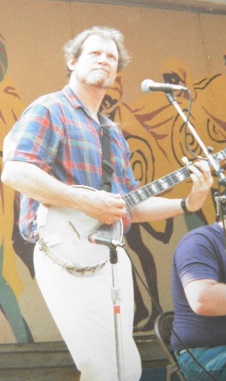

“Charles William Thompson (Tommy Thompson), banjo player: born St Albans, West Virginia 22 July 1937; married (one son, one daughter); died Durham, North Carolina 24 January 2003.

Tommy Thompson was one of the founders of the acclaimed string band the Red Clay Ramblers. Formed in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 1972, they recorded a series of albums on which they successfully fused old-time country, gospel and jazz influences and later worked closely with the playwright Sam Shepard on several of his film and theatrical projects.

The Ramblers originally played tunes they had learned from 78s by pioneering hillbilly acts such as the Skillet Lickers and Charlie Poole. They quickly tired of this, however, and developed a style Thompson called “new-timey music; a bridge that connects the past and present”. Their approach to this music was, Thompson noted, simple: “We like to make a big noise. We’re entertainers, not preachers or poets. We get people hoping, laughing and feeling good.”

Read More:

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/tommy-thompson-36274.html

“A Conversation with Tommy Thompson”

“The recent news of the death of Tommy Thompson (born in 1937, died January 24, 2003), bringing to an end the life of a sweet and generous friend, due to the lingering effects of an early onset of an Altzheimers-like dementia first diagnosed ten years ago, was one of the saddest pieces of news we’ve received in a long time. Ever since we first heard them in performance down at Godfrey Daniels in Bethlehem (see the March 1977 issue of The Folk Life), we were in love with the Red Clay Ramblers, and with their onstage clown prince and centre of gravity, “Uncle Wide Load.” (Tommy was, of course, a Ph.D. candidate and teaching assistant in philosophy before he got The Red Clay Ramblers van rolling, which, in some sense, made his later illness even more devastating to many of his friends.) I had a chance to spend some time with Tommy at the farmhouse of our mutual friend, Mary Faith Rhoads (there’s an interview with Mary Faith not yet up online), and after that conversation we made a date to meet with him for a taped interview, next time he was in town. Since then, we followed the progress of the Red Clay Ramblers with real pleasure as they were recognized by audiences all over the USA and in Europe, as “the finest old time string band now playing anywhere,” to quote our own summation of that still-vividly-recalled show at Godfrey’s.”

John: You used to teach before you got into music as a profession?

Tommy: Yeah. I started playing music just before I went to graduate school, back in ’61 or ’62. I started graduate school in ’63. And music was a hobby that gradually took over. I ended up teaching for four and a half years, at two different colleges. But then finally I found out we could do this full time, and I gave it up.”

“Tommy: Well, I’ve always had the attitude, in this band and in the others before that, that given a certain level of musical ability, the most important thing in a band is that a band is a social entity, and the important thing is to find people you can communicate with on a variety of different levels, that the people in it you respond to, that it makes your life more interesting to have them in it. And when Mike joined the band, it sounded good to have a piano, even though we had no conception then of what a piano might lead to in our band. We did know that the things we just jammed on were exciting, to us and to the other people who heard it. And we liked Mike, and he liked us, and so it was only after that we began to know him better, and he us, and began to hear more about what his musical background was, and what his tastes were, and began to feel what that would mean. Actually, that began before that, when Jim Watson and I first got together. I had been mostly involved in some fiddle tune bands, and we wanted a singing band. And Bill Hicks was a friend of ours, who’d been in the Fuzzy Mountain String Band, which was a fiddle tune band. And he was a good fiddler, and he was getting better. He had that Tommy Jarrell bite in his fiddling, and we liked that. So we brought him in to see if that kind of fiddle style would go with what we envisioned as a very different kind of band than Jim and I had been in. So that was an experiment, too. Where that took us had more to do with the instruments we played and how we played, more than any preconceived idea of what the music should be like. So it’s been a matter, from the very beginning, of finding what’s in the individual members, and then feeding that in.”

“Tommy: I think so. I mean, there is there is no way we can ever deny our musical past. So it will always have a very strong flavor of where we come from. Much stronger than any “pop” band that’s traditionally oriented. Like Asleep at the Wheel, or the New Riders, or the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. They’re country-oriented, too, yet rock music is the heart of what they do, and what they do is flavor it with country. I think we’re more strongly steeped in the country, traditional sounds than they are, and we’ll never lose that. Occasionally I’ll hear one of our pieces on the radio, on a commercial station, along with whatever else is being played on that day. And it’s then that I hear how traditional, how mountain-oriented, we really are. We come to a folk festival, or to a bluegrass and old-timey festival like this one, and we get the feeling of being very “far out,” of tryin’ to be uptown or somthin’, and I like that feeling, too. It’s exciting to be singled out that way. And yet you hear it in another context, it’s very string-band sounding!

John: Yeah. I think especially the shape-note hymn singing you do—

Tommy: We’ll never lose that.

John: Where does it come from:

Tommy: Well, for instance, “Long Time Travelling” is one of those that’s in more than one of the old shape-note books. I think we got it from “The Christian Harmony,” where it is called “White,” after its composer, B. F. White, one of the composers of many songs like that.

J. The one on the new album—not the concert you just did—is “Daniel Prayed.”

Tommy: We didn’t get that one out of one of the shape-note hymn books—not one of the canonical books. This is from an old Baptist hymnbook, and I can’t remember the name of it offhand. The first time I ever heard it, it was Doc Watson, Clint Howard and Clarence Ashley recorded it on one of those old albums they did. We heard it later, and then a friend of mine discovered it in an old hymnbook. It was almost the identical arrangement, and we got that from the hymnbook, plus whatever influence those guys had on us. Our conception of harmony singing has always been different from that of bluegrassers. In bluegrass, the ideal has always been to find people whose voices are as similar as possible. When you get that really beautiful clean blend—that’s why brother bands always worked as well in bluegrass. Just physiologically, the voices, even if one were higher than the other, they’ll still have the same timbre—

J. Genetically, being brought up in the same family?

Tommy: Right. What we have are five people with completely different voices, so when we put together a harmony part, what we’re –it’s more like –take somebody orchestrating a classical piece; you have your woodwinds, you’ve got your strings, you have your brass over here. And they all have different voices. The idea is to see how you blend those all together so that you get a unified sound. Whereas in a bluegrass band, it’s as if they’re all brass, or strings, or all woodwinds. So our harmony is different. In a way, it’s rougher, it doesn’t have that pure blend. We like it because you have more variety. Even when you sing the same parts, you can take any three guys out of the five, say, and sing the same parts, and it comes out different. And we’re able to choose which three will make the right sound for that one song.”

Read more:

http://www.thedigitalfolklife.org/Tommy.htm