Great Philadelphia Wagon Road, Ancient Roads all of them lead home, European immigrants to the Southern wilderness

From O’Henry Magazine.

“Ancient Roads

Wherever in the world they happen to be, all of them lead home

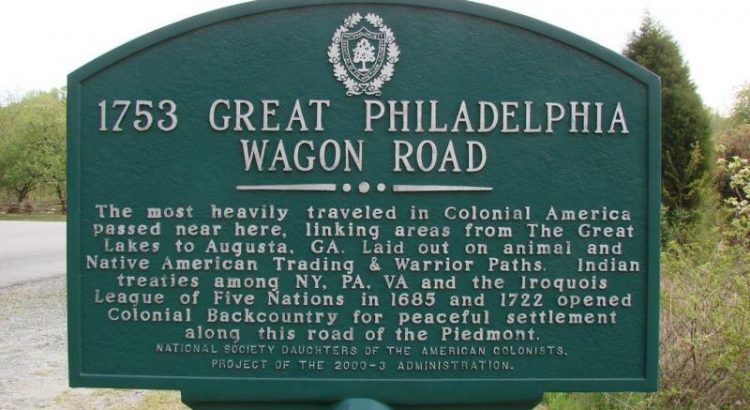

Over a year ago I began traveling the route of the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road, said to be the most traveled road of Colonial America, the frontier highway that brought a quarter of a million

European immigrants to the Southern wilderness during the first two-thirds of the 18th century.

From 1700 to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, successive waves of German, Scotch-Irish, English, Welsh and Swiss immigrants — many of them refugees fleeing their war-ravaged homelands — found their way to the Southern backcountry following an ancient trading path used by Native American tribes for millennia.

The Great Road, as I prefer to call it, stretched from Philadelphia’s Market Street to Augusta, Georgia, traversing the western portions of half a dozen colonies before crossing the Savannah River in Georgia.

Both wings of my family (and quite possibly yours) came down it — my father’s English and Scottish forebears who settled around Mebane and Hillsborough in the mid-1700s followed by my mother’s German ancestors, who hopped off the road in Hagerstown and migrated into the hills of what would later become West Virginia.

In one way or another, much of my life has been spent traveling major sections of this old road from the Carolinas to western Pennsylvania, for either work or pleasure or when I left my native South for two decades to live on the coast of Maine.

The route of the original road is buried beneath modern highways, towns and cities, suburbs and shopping centers, but it is still with us — a pathway fully determined by extensive research by scholars, state archivists, local historians and organizations that specialize in finding historic lost roads. As one leading old road researcher put it bluntly to me, “The Great Wagon Road is the granddaddy of America’s lost roads — the reason we’re all here.”

I first heard about it on a winter day in 1966 when my father took my brother, Richard, and me to shoot mistletoe out of the oak forest that grew around our grandmother’s long abandoned home place off Buckhorn Road near Chapel Hill. On the way home, he showed us the site of his great-grandfather’s gristmill and furniture shop where I-40/85 now crosses the historic Haw River. That man’s name was George Washington Tate. A street in Greensboro is named for this rural polymath who helped establish Methodist churches toward the foothills and made such beautiful cabinetry. Surviving pieces are displayed in important decorative art museums across the South.

From that day forward, I’ll admit, I was quietly obsessed with the Great Road, germinating a plan to someday travel the road of my ancestors just to see what they had seen of early America’s landscape.

It only took me a half-century to finally get around to making the journey.

My original thought — silly me — was to drive the full 800-plus miles of the Great Road over several unhurried weeks beginning in late summer of 2017, stopping to investigate the historic towns and villages along the way, checking out the important battlefields and burying grounds, equal parts listening tour and journalistic inquiry, learning whatever I could about the most important road of early America. After years of preparation — reading everything from colonial histories to the biographies of Founding Fathers, academic monographs to personal journals, and building a network of experts and contacts along the way — my larger hope was to meet people for whom the Great Road is a living passion and see how the culture of the Great Road had shaped their lives — and mine.

In theory, it was a nice approach. With the exception of one problem.

By my fifth day out, I’d only reached Amish country east of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, just 60 or so miles from the start of my journey in Philadelphia, when I realized something. There was so much unique history and culture arrayed along this pioneer pathway — to say nothing of colorful characters, great local food, quirky hometown events and tacky roadside attractions that appealed to my inner coonskin-capped kid — there was simply no way three weeks could possibly do the old road justice.

No less than seven American presidents, after all, were either born on or near the Great Road and at least a dozen key military engagements from our country’s two primary wars happened on it — Kings Mountain and Guilford Courthouse during the American Revolution, Antietam and Gettysburg during the Civil War.

After 10 days out in my own vintage “wagon” — a 1996 Buick Roadmaster Grand Estate, the last true station wagon built by Detroit — I rolled home with a full notebook and a revised plan to travel and research the road in segments of three or four days at a time.”

Read more:

http://www.ohenrymag.com/simple-life-23/