Martin Luther trial, Hearings before Diet at Worms on charges of heresy, Reformation catalyst, Questioned church sale of indulgences

“The Trial of Martin Luther: An Account

(Luther’s Hearings Before the Diet at Worms on Charges of Heresy)

Historians have described it as the trial that led to the birth of the modern world. Before the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and the Diet of Worms in the spring of 1521, as Luther biographer Roland H. Bainton noted, “the past and the future were met.” Martin Luther bravely defended his written attacks on orthodox Catholic beliefs and denied the power of Rome to determine what is right and wrong in matters of faith. By holding steadfast to his interpretation of Scripture, Luther provided the impetus for the Reformation, a reform movement that would divide Europe into two regions, one Protestant and one Catholic, and that would set the scene for religious wars that would continue for more than a century, not ending until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

Martin Luther’s long journey to Worms might be said to have begun in 1505 on a road near his home town of Erfurt in Saxony (now part of Germany), when a bolt of lightening knocked Luther to the ground. Luther took the lightening to be a call from God, and–to the disappointment of his father, who hoped he would become a lawyer–, took vows at an Augustinian monastery to begin a profoundly Christian life. Luther impressed his superiors at the Erfurt monastery. By 1507, he was an ordained priest and had offered his first mass. By 1508, he had earned a degree in Biblical studies from the University of Wittenberg and become an instructor at that Augustinian institution.

Questioning the Sale of Indulgences

A trip to Rome in 1510 caused Luther to begin to seriously question certain Catholic practices. The opportunity for the trip arose when Luther was selected as one of two Augustinian brothers to travel to the Eternal City to help resolve a dispute within the order that called for resolution by the pope. What Luther saw in Rome disillusioned him. As he watched incompetent, flippant, and cynical clergy performing their holy duties he began to experience doubts about the Catholic Church. He wrote after his journey that he had “gone with onions and returned with garlic.”

Those early doubts concerning Rome and its ways would blossom over the next several years after Luther earned the prestigious post as Doctor of the Bible at Wittenberg University and undertook a thorough review of the source book of his religion. Luther’s study led him to the theology of Paul and his belief in the possibility of forgiveness through faith made possible by the crucifixion of Christ. In Paul’s theology, which Luther would largely adopt as his own, there was no need to look to priests for forgiveness because, to those who believed and were contrite, forgiveness was a gift of God.

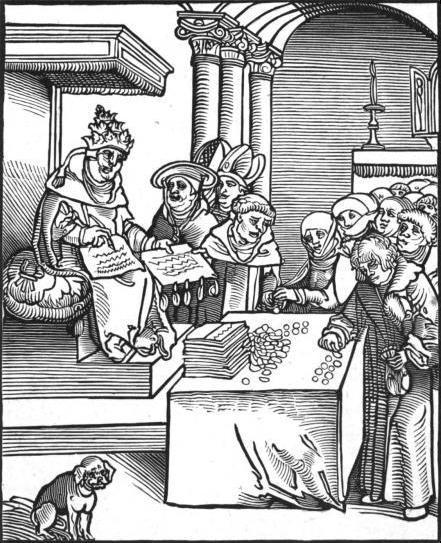

Luther’s understanding of Paul’s theology led him to view skeptically the Catholic Church’s reliance on the practice of selling indulgences as its major source of revenue. (An indulgence was a remission of temporal punishment after a confessor revealed sin, expressed contrition, and made the required contribution to the Church.) In sermons in Wittenberg beginning in 1516, Luther argued that forgiveness came from within, and that no one–whether a priest or a pope–was in position to grant forgiveness because no one can look into the soul of another. He also questioned whether the pope could, as he claimed, deliver souls of a confessor’s dead loved ones from purgatory. By lashing out at the sale of indulgences, Luther was striking at the heart of the Church’s array of money-raising tools and confrontation was inevitable.

Matters began to come to a head the next year when Pope Leo X launched an indulgence-driven campaign to raise funds for construction of a grand basilica of St. Peter’s in Rome. The practice of the time was to grant the privilege of selling indulgences to various bishops, who would retain for themselves and their purposes a portion of the raised funds. Albert of Brandenburg, granted an indulgence franchise in his territory for eight years, told his indulgence vendors that they could promise purchasers a perfect remission of all sins and that those seeking indulgences for dead relatives need not be contrite themselves, nor confess their sins. Proclamation of the indulgence fell to an experienced Dominican vendor named John Tetzel, who journeyed from town to town around Albert’s territories. Tetzel would follow a cross bearing the papal arms into a town’s marketplace and launch into a sermon, or sales pitch, that included a jingle that Martin Luther found especially objectionable:

As soon as the coin in the coffer rings,

The soul from purgatory springs.

Luther, in an angry response to the indulgence sales campaign, prepared in Latin a placard consisting of ninety-five theses for debate. The placard, in accordance with the custom of the time, was placed upon the door of Wittenberg’s Castle Church . The power of pardon, Luther contended in his Ninety-Five Theses, was God’s alone. If, indeed, the pope had the power he claimed, Luther asked why he didn’t simply exercise it: “If the pope does have the power to release anyone from purgatory, why in the name of love does he not abolish purgatory by letting everyone out?” Luther’s complaints also went to the Church’s justification for promoting contributions. He complained about “the revenues of all Christendom being sucked into this insatiable basilica” when there were much greater needs, including “living temples” and local churches.

When a copy of Luther’s theses reached Rome, the pope, according to some accounts, said: “Luther is a drunken German. He will feel different when he is sober.” Nonetheless, the pope saw Luther as sufficiently threatening to appoint a new general of the Augustinian order in the hopes that the he would “smother the fire before it should become a conflagration.” Surprisingly, however, at the gathering of Luther’s chapter that year in Heidelberg Luther’s arguments met with enthusiasm among the younger Augustinians and mere head-shaking among the older attendees.

Encouraged by the reception to his views, Luther aimed at new targets. He challenged the power of the Church to excommunicate its members, writing that only God could sever spiritual communion. He also questioned the primacy of the Church in Rome, suggesting that there was a lack of historical support for putting its authority above that of other churches. Clearly, the pope began to understand, Luther was more of a threat that he first thought. The pope turned to Dominican Sylvester Prierias, Master of the Sacred Palace at Rome, to draft a reply to Luther’s arguments. Prierias’s reply branded Luther a heretic and, gratuitously, called him “a leper with a brain of brass and a nose of iron.” On August 7, 1518, Luther received a citation to appear in Rome to answer the charge of heresy.”

“It took three months for the papal bull to reach Luther in Wittenberg. The day after receiving a copy of the pope’s bull, Luther wrote to a friend, “This bull condemns Christ himself” and that he was now “certain the pope is the Antichrist.” Luther, thoroughly aroused, unleashed a defense of his assertions that received condemnation in the papal bull in his Against the Execrable Bull of the Antichrist. The tone of his tract was defiant:

It is better that I should die a thousand times than that I should retract one syllable of the condemned articles. And as they excommunicated me for the sacrilege of heresy, so I excommunicate them in the name of the sacred truth of God. Christ will judge whose excommunication will stand.

On December 10, 1520, Martin Luther and some of his university supporters gathered at Wittenberg’s Elster gate where various theological works and documents from Rome were placed in a pile and lit on fire. Luther himself tossed the papal bull into the blaze . “Since they have burned my books, I burn theirs,” he said.

With Luther in obvious defiance of his demand for recantation, Pope Leo excommunicated Luther on January 3, 1521. Managing the Luther case for Pope Leo was the papal nuncio, Aleander . In Aleander’s view, secular tribunals had no role to play. Luther had been found guilty of heresy, condemned by the Church, and the only job of secular authorities should be to carry out the Church’s decision. “The only competent judge is the pope,” Aleander wrote.

When Luther’s Appeal to Caesar reached Emperor Charles V, he tore it up and trampled on it. Within a month, however, a more composed Charles V, concerned with the reaction of the German people if Luther were to be condemned without a hearing, reconsidered his decision. On March 11, 1521, the emperor sent to Luther an invitation to come to the Diet meeting at Worms to “answer with regard to your books and your teaching.” The emperor’s mandate promised safe-conduct if he would arrive in Worms within twenty-one days. “You have neither violence nor snares to fear,” the letter said.

Luther decided to go. In a letter to Frederick the Wise, Luther explained his thinking: “I will go even if I am too sick to stand on my feet. If Caesar calls me, God calls me. If violence is used, as well it may be, I commend my cause to God.””

“Luther would not back down. Only if he could be convinced of his errors on the basis of Scripture might he offer a retraction and “throw my books into the fire with my own hand.” He warned those judging him to not “condemn the Divine Word” lest God send down upon them “a deluge of ills, and the reign of our noble young emperor, upon whom, next to God, repose all our hopes, be speedily and sorely troubled.” He ended his speech by entreating the emperor and the lordships to not let “my enemies to indulge their hatred against me under your sanction.”

Eck found Luther’s answer evasive. He asked again, “Martin–answer candidly and without horns–do you or do you not repudiate your books and the errors which they contain?”

Luther replied, “‘Since then your imperial majesty and your lordships demand a simple answer, I will give you one without teeth and without horns. Unless I am convicted of error by the testimony of Scripture or by manifest evidence…I cannot and will not retract, for we must never act contrary to our conscience….Here I stand. God help me! Amen!””

Read more:

http://www.famous-trials.com/luther/286-home