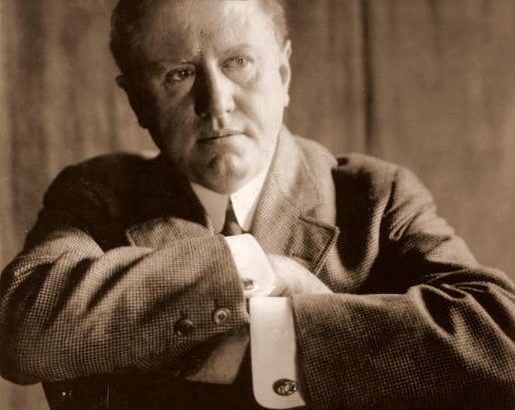

William Sydney Porter aka O’Henry Greensboro, NC native secret life revealed, One of best short story writers, “The Gift of the Magi” conceived and written in longhand in only two hours under pressure, Innocent of embezzlement?

From O’Henry Magazine.

“The Secret Life of William Sydney Porter

How the master of the short story became O.Henry

With his life in shambles, Will Porter — later to become known as O.Henry — boarded a train at the International–Great Northern depot in Austin, Texas on April 22, 1898, heading to prison in faraway Columbus, Ohio, to serve a five-year sentence for embezzlement. But that was not the only difficulty that the 35-year-old former bank teller and talented, though relatively unknown, writer and cartoonist confronted. Athol, the young Austin woman whom he married in 1887, had died the previous summer of tuberculosis — the same disease that had taken her father and Porter’s mother. This meant Porter’s 8-year-old daughter Margaret would have no parent at her side for the foreseeable future.

With Deputy Marshal Musgrave alongside guarding him, Porter had ample time during the three-day journey north to reflect upon the events beginning in 1882 that had led him from home in Greensboro to Texas and now to prison. While employed as a drugstore clerk in the downtown Greensboro pharmacy operated by his uncle Clark Porter, William Sydney Porter had developed an incessant, racking cough. At the time, the drugstore was a popular meeting place for city businessmen to gather and kibitz about goings-on in the community. One frequenter was Dr. James Hall, who took note of 19-year-old Porter’s persistent cough. Alarmed that the young man might be in danger of contracting tuberculosis, Hall urged Porter to accompany him during the doctor’s upcoming Texas vacation to visit two sons, Lee, a celebrated Texas Ranger, and Dick. The Hall brothers managed a 250,000-acre livestock ranch in south Texas. Dr. Hall reckoned a sojourn on the ranch would rid Porter of his hacking cough. Porter agreed to give Texas a try.

The doctor was right. Once on the Hall ranch, Porter’s health was rejuvenated. For the next two years, he immersed himself in the ranch’s work, relishing his role as a hand for the Halls, riding horses, sheepherding and fixing fences. But inevitably longing for more social interaction, particularly with members of the opposite sex, 21-year-old Porter decided to forego the prairie and try city life in Austin.

Once there, he cycled through several jobs: drugstore clerk, real estate company bookkeeper and draftsman for the government land office. The social Porter became a man-about-town, contributing his tenor voice to the “Hill City Quartet,” and hobnobbing with Austin’s younger set in the city’s saloons and gambling parlors. He courted several women, but it was Athol who caught his eye, and they married in 1887. It was she who now encouraged him to embrace his budding literary talent. Porter began composing short vignettes of Texas life and selling them to Eastern newspapers for modest sums.

But during his Austin days, Porter’s writing income couldn’t support a family — which by 1889 included Margaret. So when in 1891, an opening occurred for a teller at the First National Bank of Austin, Porter applied and landed the job. His lenient bosses at the bank let Porter continue moonlighting with his writing. Looking for an outlet for his talent, he purchased a failing Austin weekly newspaper, The Iconoclast, in 1895. Rechristening it The Rolling Stone, Porter served as a one-man band for the rag, responsible for writing, editing and drawing cartoons. Soon, he received recognition in local circles for his chatty jocular stories that often spoofed local figures. After a short period of being an attentive husband, Porter renewed what would become a lifelong habit of whiling away the nights in saloons and back alleys. He rationalized his behavior to Athol by claiming Austin’s diverse cast of characters provided fodder for his stories.

Porter cared little for his work at First National. It was simply a means to an end. His involvement with the newspaper he acquired, The Rolling Stone, constituted his real passion. Sensing he was on the threshold of self-sufficiency, he quit the bank in October 1894 to devote full time to the publication. But despite its artistic success, the paper capsized in a sea of red ink in April 1895 and Porter was left adrift without gainful employment. In October, the editor of the Houston Post offered the struggling Porter a life raft: a position as a “special writer” at the modest rate of $15 a week. With no other prospects, Porter pulled up stakes and relocated to Houston. Athol and Margaret temporarily remained in Austin with Athol’s mother and stepfather, Mr. and Mrs. P.G. Roach, until The Post upped Porter’s pay. But upon finally arriving in Houston, Athol began to suffer the early symptoms of her tubercular condition. Ultimately, she and Margaret returned to Austin.

Gray, a grand jury had handed down a four-count indictment in February 1896 against Porter, claiming he had embezzled a total of $4,702.94 while employed as First National’s teller. To those familiar with First National’s loose banking practices, it seemed unfair for the government to target Porter for the shortages. Routinely, the bank’s officers dipped into the till themselves, withdrawing cash without leaving IOUs. Bank policy had permitted overdrafts to these same officers. While Porter had been sloppy, too trusting of the bank officials and oft distracted by his duties at The Rolling Stone, his friends could not fathom he would be consciously dishonest.”

“Porter’s arrival in New York proved to be perfectly timed. Public demand for good short story writing in the city’s numerous literary magazines had risen to a fever-pitch. Once editors got wind of Porter’s knack for the genre, they knocked down his apartment door in efforts to publish his stories, now all under the pen name of O.Henry. And even though he was prone to missing deadlines, Cosmopolitan, Harper’s, McClure’s and Munsey’s magazines — and the New York World newspaper — remained at his beck and call. When absolutely forced to, he could churn out a story with astonishing speed. His tour de force, “The Gift of the Magi,” was conceived and written in longhand in only two hours after Porter discovered he had forgotten an obligation to the Sunday World to produce a Christmas story.

He wrote not for fame — that might cause the revelation of his dark secret — but for financial reward. He once explained that, “[w]riting is my business. It is my way of getting money to pay room rent, to buy food and clothes and Pilsener. I write for no other purpose.” But Porter seamlessly mixed his business with pleasure by roaming the “New York Tenderloin” long into the night, observing the escapades of both the high hats and dregs of the city, deriving potential story lines from these varied experiences. An incorrigible ladies’ man, he took particular delight in cajoling young shopgirls into joining him for dinner. For the price of a planked steak, he would urge the women to relate their troubles. Several stories Porter penned during his New York days involve the travails of shopgirls, no doubt gleaned from these dual-purpose encounters. In addition to his New York–based stories, Porter wrote others informed from experiences and people he encountered in Texas, Honduras and in jail.

O.Henry never quite managed to turn out a novel as several publishers urged, but collections of his short stories in such volumes as Cabbages and Kings and The Four Million became runaway best sellers. Suddenly he was being compared to the likes of Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson. Watson’s Magazine’s review of The Four Millionsummed up what many reviewers were beginning to realize: “In word limit all the stories are shorter than the average magazine story, yet it would be difficult to find as much observation and insight compacted in the short stories of any fictionist today.”

But Porter ducked away from all the plaudits. One of his editors, Robert H. Davis, remarked, “Porter fled from publicity like mist before the gale . . . shrank from the extended hands of strangers . . . and avoided conversations about himself.” On holidays from Ward-Belmont School in Nashville, Tennessee, Margaret would occasionally visit her father in New York, but Porter would keep the visits short. While Margaret may still have been in the dark, every editor in New York knew of Porter’s secret by 1907. Nonetheless, Porter kept trying to hide the secret that was no longer much of one — at least to insiders — until the end of his days.

Unfortunately for Porter, the end of his days were not far distant. Ill health began to dog him around 1907. Whether from staying out all night drinking copious amounts of whiskey or contracting some unexplained sickness, he found himself in a perpetual state of malaise. His deteriorating health may explain how he came to lean on a woman from his Greensboro youth. As a teen, Porter had been periodically smitten with an Asheville girl who was summering in Greensboro with relatives. Sara Coleman had faded out of Porter’s life once he moved to Texas. Suspecting that Will Porter and O.Henry were one and the same, she wrote to him in 1905, and a mutual correspondence ensued. The writings became more intimate as time went by, and Sara eventually visited him in New York in September 1907. Before she returned home, Porter had proposed marriage. Before she responded, he haltingly wrote her and revealed his problematic past. She accepted his proposal anyway. They were married in Asheville two months later. Porter had the best of intentions to reform his late night ramblings. “I’ve had all the cheap bohemia that I want,” he told a friend “It’s for the clean, merry life . . .”

But the marriage seemed less a romantic union than a dependent one, with Sara filling more of a mothering and nursing role. She convinced her husband to move out to Long Island, where he presumably would not be tempted to partake of the saloon life. Margaret, now an aspiring writer and winding up her education at a girls’ school in New Jersey, would be able to spend her summers with the newlyweds. Inevitably, Porter chafed at the peacefulness of his surroundings, and his wife’s unceasing efforts to get him to mend his ways. Like a moth to the flame, he was ultimately lured back to the bright lights of the city. Bearing little acrimony, the couple separated, with Sara moving back to Asheville.

Plunging back into the city’s nightlife doomed any chance of restoring Porter’s health. By midsummer of 1909, he was too sick to work and he reluctantly decamped to Asheville where Sara checked him into a sanitarium. But once feeling better, Porter again could not resist returning to New York. His condition promptly regressed. At the peak of his fame, Porter, 47, found himself alone with no family alongside at the city’s Polyclinic Hospital, where he had been diagnosed with kidney failure, cirrhosis of the liver and diabetes. On Saturday, June 5, 1910, a nurse stopped by Will Porter’s room at midnight to turn off the light. “Turn on the light,” he pleaded. “I’m afraid to go home in the dark.” This served as O.Henry’s personal surprise twist to his own ending. He died later that morning.”

Read more:

http://www.ohenrymag.com/the-secret-life-of-william-sydney-porter/