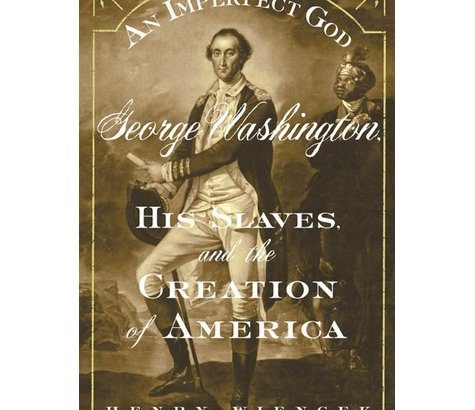

George Washington an Imperfect God by Henry Wiencek, Washington’s attitudes began to change on battlefields, Saw system’s evil before presidency, Freed slaves in will

From Amazon.

“When George Washington wrote his will, he made the startling decision to set his slaves free; earlier he had said that holding slaves was his “only unavoidable subject of regret.” In this groundbreaking work, Henry Wiencek explores the founding father’s engagement with slavery at every stage of his life–as a Virginia planter, soldier, politician, president and statesman.

Washington was born and raised among blacks and mixed-race people; he and his wife had blood ties to the slave community. Yet as a young man he bought and sold slaves without scruple, even raffled off children to collect debts (an incident ignored by earlier biographers). Then, on the Revolutionary battlefields where he commanded both black and white troops, Washington’s attitudes began to change. He and the other framers enshrined slavery in the Constitution, but, Wiencek shows, even before he became president Washington had begun to see the system’s evil.

Wiencek’s revelatory narrative, based on a meticulous examination of private papers, court records, and the voluminous Washington archives, documents for the first time the moral transformation culminating in Washington’s determination to emancipate his slaves. He acted too late to keep the new republic from perpetuating slavery, but his repentance was genuine. And it was perhaps related to the possibility–as the oral history of Mount Vernon’s slave descendants has long asserted–that a slave named West Ford was the son of George and a woman named Venus; Wiencek has new evidence that this could indeed have been true.

George Washington’s heroic stature as Father of Our Country is not diminished in this superb, nuanced portrait: now we see Washington in full as a man of his time and ahead of his time.”

https://www.amazon.com/Imperfect-God-Washington-Creation-America/dp/0374529515

From the Introduction.

The General’s Dream

“Before dawn one summer morning at Mount Vernon, George Washington awoke from a troubling dream. It was 1799, the last year of the general’s life, and he was finally savoring the fruits of retirement. But the serenity of that summer was abruptly shaken by the dream.

Martha had awakened first, and had just risen from the bed when Washington stirred and spoke to her. She could tell at a glance that an uncharacteristic sadness had settled upon her husband in the night.

He had dreamed, he told her, that they were sitting and talking about the happy life they had spent together and the many more years they would have in each other’s company. In the dream “a great light” suddenly surrounded them; and from the light there emerged the barely visible figure of an angel, who stood at Martha’s side and whispered in her ear. As the angel spoke, Martha “suddenly turned pale and then began to vanish from his sight and he was left alone.”

The dream seemed to foretell that Martha would be taken from him, but Washington grasped a different meaning: he said to her, “You know, a contrary result indicated by dreams may be expected. I may soon leave you.”

Alarmed, Martha tried to comfort him by forcing a laugh at “the absurdity of being disturbed by an idle dream,” but her efforts were in vain. The dream became “so deeply impressed on his mind that he could not shake it off for several days.”

Washington was a fatalist; he feared nothing, not even death. If his time had come, then it had come. The grimness Martha discerned arose not from fear but from a seriousness of purpose. He took the dream as a sign that he had to settle certain accounts before time ran out. From some scraps of paper she came across in his study, Martha soon discovered that, in the wake of his troubling dream, her husband had begun to write his last will.

“In the name of God amen I George Washington of Mount Vernon – a citizen of the United States, and lately President of the same, do make, ordain and declare this Instrument; which is written with my own hand and every page thereof subscribed with my name, to be my last Will & Testament, revoking all others.” The document was eventually to run to twenty-nine pages and would carefully enumerate bequests to some fifty relatives – a tangled family tree that Washington, like all Southern patriarchs, kept committed to memory.

In the first, one-sentence item, he provided for the needs of “my dearly beloved wife Martha Washington” for as long as she might live. But after this customary clause, Washington turned to the subject that clearly was uppermost in his mind, to which he had given a great deal of thought for a long time. With his next words George Washington renounced the system that had nurtured him and given him wealth: “Upon the decease of my wife, it is my Will & desire that all the Slaves which I hold in my own right , shall receive their freedom.” After writing that plain declaration, Washington filled almost three pages with explicit instructions for the manner in which his slaves should be freed. He specified that the children should be educated and trained so that they could support themselves as free people.

It was an astounding decision. As he sat in his study – a room that one visitor called “the focus of political intelligence for the new world” – Washington felt the isolation of the man who can see what others cannot or will not. He was a man who had discovered that his moral system was wrong. He had helped to create a new world but had allowed into it an infection that he feared would eventually destroy it.

No other Founding Father would set his slaves free, and certainly none of them contemplated educating slaves as Washington did. The traditional planter’s definition of benevolence presumed holding the slaves in humane but firm bondage, and the schooling that some favored slaves received was intended not to fit them for independence but to make them more useful to the master. To understand how extraordinary Washington’s decision was, one has only to look at the pronouncements of other Southern Founding Fathers on the subject of slavery. A fellow Virginian, Patrick Henry, wrote of the slaves, “let us treat the unhappy Victims with lenity, it is the furthest advance we can make towards Justice.” Thomas Jefferson scoffed at the very notion of emancipation: “To give liberty to, or rather, to abandon persons whose habits have been formed in slavery is like abandoning children.” Washington thought otherwise.

In his last months, Washington struggled with the paradox that continues to vex us today: how is it that the nation – conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal – preserved slavery? The word “paradox” suggests abstraction, a debate in a gathering of bewigged white gentlemen. But Washington’s will reveals that, in the stately chambers of Mount Vernon, his struggle over slavery was played out in a sharp family conflict.

The emancipation clause stands out from the rest of Washington’s will in the unique forcefulness of its language. Elsewhere in it Washington used the standard legal expressions – “I give and bequeath,” “it is my will and direction.” In one instance he politely wrote, “by way of advice, I recommend it to my Executors …” But the emancipation clause rings with the voice of command; it has the iron firmness of a field order: “I do hereby expressly forbid the Sale … of any Slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever.” This plainly implies that Washington expected that pretenses would be made and slaves would be sold once he was gone. Furthermore, Washington commanded his family “to see that this clause respecting Slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled … without evasion, neglect or delay” (the emphasis is Washington’s). Nowhere else in the document did he speak with such vehemence. The force of his commands makes it clear that within his own family Washington was entirely alone in his thinking about slavery. He expected that the emancipation would come as a shock to his family and, moreover, he expected them to resist it. Washington was positioning himself as the protector of his slaves.

Washington’s emancipation of his slaves at Mount Vernon has long been dismissed as a mere parting grace note, of little significance except as a mark of his inherent benevolence. But the will hints at a profound moral struggle; indeed, his decision to free his slaves represented a repudiation of a lifetime of mastery. For his entire life he had been conditioned to be indifferent to the aspirations and humanity of African-Americans. Something happened to change him and to set him radically apart from his peers and his family.

Crossing the barrier into the past is treacherous, but the journey is doubly difficult if one is seeking to understand a man as elusive, as contradictory, but as critically important as George Washington. “As to the inner man we are strangely ignorant,” one historian wrote, “no more elusive personality exists in history.” A French visitor remarked, “an atmosphere of silence envelops the deeds of Washington.” Even in his own time, Washington’s achievement surrounded him with a blinding, almost divine radiance that made the man himself seem unapproachable. Watching him as he merely walked down the street, Abigail Adams could almost feel the ground tremble under the shoe of the man who appeared “as awful as a god.” Once when he entered a room full of his step-granddaughter’s friends, apparently eager for an informal chat, all conversation instantly ceased. The step-granddaughter recalled that because of “the awe and respect he inspired … his own near relatives feared to speak or laugh before him.” On the occasions when his presence chilled a social event, “he would sit a short time and then retire, quite provoked and disappointed.” Then and now his unique eminence arises from his sterling personal qualities, from the inescapable fact that we Americans owe everything we have to him, and from the eerie sense that, in him, some fragment of divine Providence did indeed touch this ground.”